The Balance of Skills Necessary for a Contemporary Design Practice with Dan Mall

In this episode Dan Mall founder and design director at SuperFriendly joins Gary Rozanc to discuss the ever changing role of interactive designers from simply designing visuals to not only needing to understanding an organization’s goals, but help identify new goals beyond visual design and sell the clients on that vision. The conversation also goes into details on the approach of traditional four-year university level graphic design education vs. apprenticeships, and the necessary skills, from software to business, that students will need to be industry ready.

Dan Mall is an art director & designer from Philadelphia; Founder & Design Director at SuperFriendly; co-founder of Typedia, The Businessology Show, and No Chains. Dan was formerly Design Director at Big Spaceship, Interactive Director at Happy Cog, and a technical editor for A List Apart.

Dan has worked with clients like Google, Lucasfilm, Microsoft, GE, Wrigley, The Mozilla Foundation, Thomson Reuters, and The Sherwin-Williams Company. Dan has done presentations at conferences like SXSW, Future of Web Design, and An Event Apart, which is where I first met Dan.

He’s also taught at the Miami Ad School, the University of the Arts, and the School of Visual Arts and was recently chosen to be a "net Magazine" awards judge.

Episode Links

Abridged Transcript

- Gary Rozanc

- So, the first thing I wanted to ask you about is I saw your presentation, “So What Do I Make?” at An Event Apart: Atlanta, and it was covering your working process, your design process and how it’s changed to meet the demands of modern communications and how we create those designs. That’s probably a gross generalization of your presentation.

- As I was watching it, since I’m a design educator, I was looking at that process that you were doing and I just felt like I’m not teaching that same process anymore, I’m still teaching this print-heavy, visual, everything-all-in-one-page process. So, can you elaborate on your process for the listeners and then talk about why you made these changes?

- Dan Mall

- Yeah, sure. I’m happy to. So, I think the world has changed in the last couple of years in a way that I think is fantastic. If somebody from 100 years ago dropped into our present, they would have no idea what was going on. And even from 5 years ago, 10 years ago, the idea of accessing a website or accessing anything digitally, traditionally you’d have to sit at a desk and sit in front of a big screen, and traditionally the bigger your screen, the better off you were doing, and that’s the way that you got information, especially from the internet.

- In the last 5 or 10 years, that has changed drastically, where people are getting information in devices that fit in their pockets. And third world countries are connecting to first world countries in that way. It’s really changed how the world works. I read a stat from McKinsey, that by 2025 the global economy will be changed by $3 trillion because of the impact of mobile. If designers don’t really understand that, you’re missing a big thing in the world.

- So, I think the role of the designer has changed from a couple of years ago, where a designer was mostly just like, “Make this look pretty, make this look good,” and I think there are a lot of designers that do that, both intentionally and unintentionally, and I think that the ones that are moving past that are going to have better jobs, they’re going to have more shelf life, they’re going to have more relevancy at the jobs they do if you can understand that design is more than just making things look pretty.

- I think my favorite definition of design is from my friend Jared Spool, and he says, “Design is the rendering of intent.” I love that definition because it certainly encompasses things like graphic design, but it also encompasses things like system design and just thinking about how things should work and how things should be. I think that’s really the role of a designer, and so I think that’s what designers should be doing in processes, whether they’re building websites, or making apps, or changing a business, or figuring out how a city should run, or designing a subway system. I think all of those things are just about learning how things should work and really being intentional about how those things work. The thing that I talk about in my talk is how does a designer shift their own mindset and also shift the mindset of the people that are hiring with them and working with them from, “You’re just the person who makes things pretty,” to “You’re the person that can help me think through all of this stuff.”

- Gary

- As a design educator, we train them how to make things look pretty and we do our best that we can to teach intent, and I think we always have taught intent, but I think what’s changing now is 10 years ago it was—and I’m making this up as I go—but 80% what it looked like, 20% intent, where now I think that’s almost completely flip flopped. So, I’m just wondering, from your perspective, how much should a design educator be teaching to make it look good, to make it visually appropriate but also teaching about intent and teaching about audiences and teaching about, “Is this the best solution for the problem that’s being presented?”

- Dan

- Right. Yeah, I mean, it’s tough because I think part of the job of an educator, especially when you’re talking about undergrad—if you’re talking about higher education—is you have to teach fluency, because you can’t render intent if you’re not fluent in the format or in the medium. And so, if somebody is trying to, for example, design something that helps you pay your taxes but they keep encountering a bug in Photoshop, it impedes their ability to render intent. So I think part of the job of an educator, especially in undergrad, is to teach fluency, and so you have to teach, “Here’s how you make things look good, here’s how you get your head around the tools, here’s how you become fluent,” at the point where you stop fighting the software and at the point where you’re like really fluent in it. Then you can start thinking more deeply and at a higher level about what you’re actually doing. But if you’re in there, you’re trying to design a subway system and you don’t know what the marquee tool does, it’s going to impede your ability to do that.

- My friend Ben Callahan, who runs an agency called Sparkbox, he has a great metaphor for this. He talks about this in the way that jazz musicians play music. A lot of people think that jazz musicians are informal musicians, like “Oh, they just play what they want and they improvise.” But that’s not actually true. Jazz musicians often know their music way, way more intimately than, say, classical musicians do and they know where they can deviate, and they know when to come back. But they know it so fluently that they can sort of wing it, and they can come back to it, they can come back to the theme when they need to, they can improvise when they need to, and it’s because they know their music so well that they can sort of deviate from it and decide where to take a tangent and then decide where to come back to the theme.

- Gary

- I have a couple of questions about, again, your working process. When I teach a web design class, after they do their initial research of who they’re designing for; I have them gather content first so they know what they’re going to be designing and who they’re designing for… I go into wireframes, then we go into Photoshop mockups, and then we start doing HTML and CSS mockups, proof of concept, before we get into final production. But you have a different process, and I’m actually really fascinated by this idea of element collages and style tiles and how they kind of are replacing that, “Let’s design an entire web page mockup and show that to the client.” Can you talk about that a little bit?

- Dan

- Yeah, sure. So, in the talk that you’re referencing, I kind of break down what I think a modern designer’s workflow could be and certainly not should be, because I think everybody designs in a different way and you can go any sort of way that feels good to you, that feels comfortable. I think that’s key #1, is if you’re not comfortable doing it, you’re not going to do a good job. So, if you’re comfortable doing a waterfall process, great. Do that and do that to the best of your ability. If there are holes in it to you and you’re more comfortable doing something else, you should do that. So, I think the subtext of all of it is design a process that really works for you and works for whoever you’re designing for: your client, your boss, your coworkers, or whoever it is—or your teachers or anything like that.

- The talk that I do is mostly, “Here’s what works for me,” and maybe people get something out of that and maybe it could inspire them in their process, but I’m certainly not prescribing it as, “All designers need to work this way because this is the way that it’s supposed to go.” So for me, the way that I like to work is a little bit backwards than the way that I learned, where when you learn to design, you learn to do a lot of work. You jump in right away. You sketch, you make wireframes, you do sitemaps, you do graphic design, and there isn’t a lot of emphasis on the thinking part of it. And you spend a lot of time making a lot of mistakes, and making good mistakes and making bad mistakes, and doing rounds and rounds of comps and doing all sorts of stuff like that.

- What I found in my work is actually the more I plan up front, the easier it is for me to execute something. So, I kind of break it down into four pieces of a design framework. The first piece is that I think designers should plan more. The second piece is that I think the designer should inventory more. The third piece is I think that the designer should sketch more. And the fourth piece is I think that designers should assemble more. So, I won’t go into the details of all of that just because I think we would be here for two hours…

- But I think if you spend time planning, and what that means to me is I spend a lot of time writing before I design. Like, as a good design exercise, I write about what I’m trying to accomplish, and sometimes I’ll share that with a client and sometimes I won’t, sometimes it’ll just be kind of a manifesto for myself, but it grounds me and centers me in what I’m actually trying to achieve. And so I write through that stuff and I try to articulate it, because then if I can describe it to myself, I’m essentially giving myself instructions on the graphic design part. So if I can write it, I just use it as a set of guidelines for myself when I get to comping. And so I think when you plan more and when you inventory more and you sketch more, and by sketch I mean certainly pencil and paper but also doing prototypes and really try to approximate things before you’re doing the final thing, it makes doing the final thing really, really easy at the end.

- So for me, if I’m doing a six-month-long project, I’ll spend three or four of those months just planning, just playing around, sketching, thinking, brainstorming, writing. And then in the last two months is when I’ll do all of the assembly work, because if I’ve made all the pieces that I need, if I’ve made 100 prototypes of all the different things, if I’ve done 1,000 sketches, if I’ve written 40 documents that guide my work, then putting it together is the easy part. And so that’s kind of what I’ve found has been really useful for me, is the time of doing something is sort of the easy thing. The time figuring out what you need to do—that’s the hard part. So, I’ve been doing this for a while now and so I have fluency with my tools, so I don’t fight the tools anymore. But when I sit down in front of Photoshop and I’m like, “What do I make?” that’s the hard part. So, I want to really focus on planning that stuff out before I get to that point so that by the time I sit in front of Photoshop, I know exactly what I’m going to do and I can bust it out in 30 minutes.

- Gary

- About your process, to go back to that, again, those element collages. What was important for me—I think I was listening to your podcast with Brad, and you were talking about the conversations, the element collage when you design this navigation, and you don’t show it in full context, ends up creating a conversation with the client. That, to me, is really important. I’m just curious if you have any suggestions… how could I recreate those kinds of client conversations in the classroom? Because when you’re in the classroom, students are talking to other design students, they’re talking to design professors, and it’s not the same thing. You don’t have those same type of conversations that you would with a client. Do you have any suggestions how to build that into a class or into a project?

- Dan

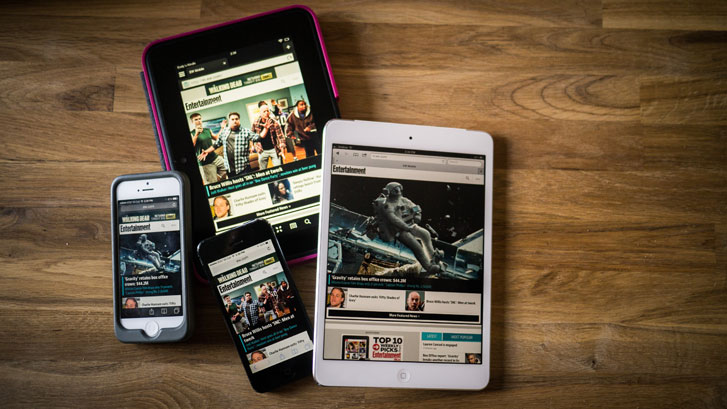

- Yeah, absolutely. So, I have three suggestions and hopefully by the time I finish them I will remember all three. The first one is—you mentioned context, and I think what led me to doing an element collage was I realized there are many contexts. So, I’m not designing for an iMac. That’s one way that somebody would access the site. But another way is somebody would access it on an iPad, and another way is somebody might pull it up on their TV using their PS4. And another way is that they might use their iPhone, and another way is they might use their dumbphone. So the idea of context… I think we’ve assumed as web designers that there is a finite set of contexts that we can design for, and the nature of the web is that there’s not. Like, my sites now magically have to work on a watch and I didn’t design them that way. But they have to work, because that’s how people are going to access them. So regardless of what I thought… I can’t dictate that.

- So, I think the idea of freeing yourself from a context, I think I’d just make that part of the conversation. The intention of that is to say to a client, “There is no context here. So, imagine this in an infinite amount of contexts.” And in order to do that, I have to remove the context from my comp. I don’t show them iPhone chrome because that is a falsification of context. I don’t show them on an iMac, because that’s a falsification of context. So, by showing an element collage on kind of like a blank screen and it being a 4,000 pixel by 4,000 pixel document, I’m leaving it up to you to imagine this context and that conversation is going to shape that kind of structure for you. So, I think that’s one piece.

- The second piece is that sometimes you just don’t have ideas for the whole thing yet. Sometimes you have an idea for the header, and you just want to do the header. And sometimes you just have an idea for one particular box on the page, or a button, or the way that some text is going to appear, or a link style. When you design a comp, you’re forced to figure out all the things. Sometimes you’re just not ready to figure out all the things. So, what I also like about the element collage is it lets you design all the pieces that you want, and I find that’s really liberating for a designer.

- Whenever I’m coaching designers or if I’m working with younger designers, or apprentices, or students, or whatever, I’ll just say, “What do you want to design?” They’ll say, “I had this great idea for a carousel.” I’m like, “Cool, design the carousel then. Start there. Don’t worry about the rest of it,” because I find that people do their best work on the stuff that they’re excited about. Like, no one designed a footer that was great when they weren’t excited about the footer. But if somebody has a great idea for a footer, then they make it really quickly and it’s the first thing they need to get out of their heads and it ends up being awesome because that’s the thing that they wanted to design. All the rest of it is necessity.

- So, when you’re talking about working it into a project, that’s the way that I work it into a project: “What’s in your head and what do you need to get out of your head the quickest? That’s the thing that you should start with.” When you go down a comp route, the thing that you end up starting with is the homepage, because, well, where else would you start? But sometimes you just don’t have ideas for your homepage and your homepage comes out looking vanilla, but you did it because you had to get it done.

- So, I fulfilled my prophecy. I’ve forgotten the third thing here. [laughs] But those are the two things. One is remove the context and the second thing is starting with the stuff that you really want to do. One of my apprentices now, her assignment is to design a site for the apprenticeship. We didn’t do sitemaps or wireframes or whatever. I was just like, “Sketch out what you want to do,” and she sketched this progress bar that showed each apprentice and how far along the apprenticeship they are, and I was like, “Cool. Design that.” So, she’s designing that. We have no idea what the rest of the site is going to be, we don’t know what the nav is going to be, we don’t know where that fits on what page, but I was like, “That’s cool. We can figure out all that stuff later. Just design the pieces that you feel strongly about.” And it’s coming out awesome.

- Gary

- Well, you know, that actually leads into my next question, you did it for me. So, there’s a lot of—I call them pop-up schools, I don’t know if that’s necessarily the best term—but there’s a lot of schools like General Assembly and Iron Yard that are offering to teach interactive web design. I think they’re proliferating because there’s a big lack in higher education in teaching these skills in four-year institutions. So, you just mentioned it, you’re doing the same thing, you’re providing training through an apprenticeship program. What made you decide to do that apprenticeship program, and can you explain a little bit of how it works?

- Dan

- Sure. So, I’ve always been interested in teaching people and I think I’ve always been interested in that because that’s how I learned. Like, I had really, really great mentors and teachers and people that spent time with me to help me develop. And so, to me, that’s the way that people learn because that’s the way that I learned; that’s what I can empathize with best. So, my apprenticeship is sort of based around that idea. And you’re right, there are a ton of things popping up like that. There’s General Assembly, and Code School, and Codecademy, and Skillshare—like, all of these things which are really great and they’re filling needs, because people need jobs and organizations need that type of work—they need help developing things and designing things and really being prolific in a digital economy. Jeez, I can’t believe I said “digital economy”…

- …But we live in a world where people access things digitally all the time and I think those kinds of schools cater to that. But I think what they’re doing is they’re teaching trades and they’re teaching skills. So, you go to Codecademy and you learn Ruby, or you go to Code School and you learn JavaScript, and then you can do JavaScript. And I think that’s great.

- But one of the things that I think is really difficult to do online or even in short format is teach the soft skills that are necessary to make good professionals. You can learn JavaScript and be an awful employee. You can be amazing at JavaScript. You could take a bootcamp or you could do whatever and you could be great at it. But you might not be able to make a deadline, and then you’re going to get fired. It doesn’t matter how good you are at JavaScript—if you can’t meet a deadline, you are going to fail at that job. And so, those are the things that are really hard to teach, especially in an online format, or even if you’re in person and you’re doing a four-week course. It’s really hard to teach that skill; it’s really hard to teach pacing, and scoping, and pricing, and all of that stuff.

- So for me, I was looking for a way to get much deeper in training, so my apprenticeship is a nine-month apprenticeship. I look at these schools that are doing six weeks and I’m like, “Man, I wish I could do a six-week apprenticeship.” But in six weeks, you barely scratch the surface. So, it’s a nine-month apprenticeship that I do, and I generally work with people that have very little or no training at all. So, it’s not for like the junior designer who’s trying to become a senior designer. Like, that person can go get an internship somewhere. They’re not right for the apprenticeship. The apprenticeship is for the person that works at a radio station, that realizes they can’t make a career or make a good living off of making $7 an hour working at the radio station. And so they’re looking for a career or they’re looking for kind of a way out of that, or they’re looking to make a life out of it, and code or design is the vehicle to allow them to do that. So, that’s kind of what the apprenticeship is about.

- And we start from scratch. There’s two tracks right now: you can be a design apprentice or you can be a development apprentice. If you’re a design apprentice, day one is opening Photoshop and we go through every tool one by one. “This is the move tool. The shortcut key is V. It does this. If you check this box, it does this. This is a properties inspector. This is what you see here. This is your layers palette. These are called windows, these are called panels, these are called menus.” So, start from scratch. If you’re a development apprentice, we start from scratch there, too. “So, here’s a code editor. Download Sublime Text, or Atom, or whatever. Open it up. File, new. Here’s how you write your first line of HTML. This is what a tag is. These are what attributes are. This is called an ankle bracket.” You know, all of that kind of stuff, and we start at the very, very basic of all of it.

- To me, I try to be very intentional about whether or not to call it an internship or an apprenticeship or whatever, and the reason that I ended up with apprenticeship is that I’d like to get as close as I can to a medieval apprenticeship. In the medieval times, when you wanted to be a blacksmith, when you were 13-years-old you went and you lived with a blacksmith for seven years. Like, you moved into his house and he taught you how to blacksmith. But not only did he teach you that but you had to cook, and clean, and you had to clean your room and you had to clean his house. And you lived with him for seven years and you learned not only blacksmithing but you learned how to be a professional blacksmith. You learned the trade but you also learned the profession, and I think those two are different things.

- Then after seven years of being an apprentice, you become a journeyman. Like, your master blacksmith says, “Cool, you’re ready to go,” so you become a journeyman and you work on your own blacksmithing projects. And then eventually you submit the equivalent of a Master’s thesis; you submit a project to the guild of blacksmiths, and then that guild of blacksmiths evaluates your project and they say, “Yes, you are ready to become a master yourself.” And then at that point, you take on your own apprentices; you get an apprentice to come live with you for seven years. Now, I don’t want somebody to live with me for seven years, but I’m trying to get it as close to that as possible.

- So, the apprentices that I have, they’re with me all day, they’re in my studio, and they get to hear everything and they get to see everything. So, they look at my contracts, I do phone calls in the open, we do conference calls—like, I don’t have conference rooms or anything like that, I don’t do private phone calls, with the exception if maybe I have to call my doctor about something private or something like that. But everything is kind of out in the open and they learn certainly design and development, but I also strive to teach them things like, “Well, how do you price a job? And how do you meet a deadline? And how do I get work done when there’s a lot of distractions? And what’s the appropriate time to break for ping pong? What time should I wake up every morning in order to get into work?” It could be stuff as basic as that. “What do I do when I Git commit the wrong stuff and I ruin the repository?” That kind of stuff. And that’s stuff that you don’t get in online programs, just because the time is not allotted for it. So, that’s kind of what I modeled the apprenticeship after, and I try to get as close to that as possible.

- Gary

- Actually, that’s one thing that in most design programs… they also go into foundations, and this foundation is taught by artists and designers. And that’s almost my biggest complaint, is that we need to start teaching them to be designers—not the specific skills, not even the soft skills. What does a designer look, act, and feel like? So, I love that you cover that. I know your time is valuable, so I just want to ask you one more question, and it has to do with your apprenticeship and some of the things that are being taught in it. Specifically, you obviously must have seen a huge gap between being a designer and running a design business, so I think this is one of the reasons why you started your Businessology podcast show. Is this another reason why you started this apprenticeship, is that disconnect?

- Dan

- Yeah, absolutely. So, Mike Monteiro, he has a great story about this and I’ll never forget him telling me this—I forget if he said it on a podcast or if he said it just kind of in passing in a conversation. But I asked him why he writes about business, because he’s written great books and he’s written a lot about how to be a professional, and he could easily write about typography, or graphic design, or motion design, any of those things because he’s just as competent at that stuff too.

- And I said, “Well, why do you write about that stuff, and why do you talk about that stuff, and why is that your thing?” He’s like, “You know, we have a rule in our office, that if you find something that’s broken, it automatically becomes your responsibility to fix it. So, if you walk by the printer and the printer is broken, even if you’re not the printer technician, you have to fix the printer. If there are dishes in the sink, you become the dishwasher, even though that’s not your job. If you see something and there’s something wrong there, it’s your responsibility to fix it.” He said there’s a ton of people that are talking about typography and motion design and graphic design and interaction design and UX and all that stuff, but nobody was talking about business. He’s like, “So I found that, that was a problem, and so I took it upon myself to fix it.”

- I think that’s the mantra for me, as well. I was talking to my CPA about it and we both realized that we had a passion for talking about this stuff, and not a lot of people were talking about it. There was only a handful of people talking about it compared to talking about topics like user experience and graphic design and all that stuff. So, we just decided, “Well, we can do something about it.” And so we did.

- Gary

- As a design educator, I know how important it is to be able to have this business acumen. But I have mixed feelings. Is that something that should be taught in a design program—the business side of design? Because that means I’m going to now have to get rid of something, whether that’s the visual tool skills, or talking about intent. Do you feel that should be something that should be going back to design education?

- Dan

- Yes, I think so. Well, actually I think so very strongly. I don’t know if it’s worth the expense of something else, because I think we could fill a curriculum with an infinite amount of things that can be taught. So I guess if your question is more like, “In a four-year program, should I kill a Photoshop class in lieu of a business class?” I’m not sure. I don’t know, because if you don’t have fluency in the tools, I think then you’ll be missing something, that even if you sell it well, you can’t really come through on it. So, I think certainly teaching the fluency part is important. I don’t know if business is more important.

- But the reason that I’m interested in it is because I’ve been part of many processes and I’ve worked with really, really great clients and companies and agencies, and one of the things that I see across the board is that sometimes as a designer you get handed something, and you know it’s not the best way to go about it and you know it’s not going to produce the best result, but your hands are tied. So, sometimes that’s, “Here’s a style guide. You have to use this style guide.” You’re like, “Well, I could make a better thing if I didn’t have to follow the style guide…” but that’s a constraint. And sometimes you fight the good fight to push back on that style guide and see if the client will give you some leeway, and sometimes you win and sometimes you don’t. And there are all sorts of things within a process that constrain you artificially.

- I think designers work well under good constraints, but I also think there are some artificial constraints that actually designers don’t need. Sometimes, one of those constraints is, “Well, we sold this project, so we have to do this project. Even though it’s not the best thing for the client, that’s what we sold.” So for me, I was always interested in the sales part, because if we could sell the right thing, then we could do the right thing. But if we sold the wrong thing, well, contractually we are obligated to do that thing, even if it’s not the right one. And sometimes that’s when sales teams are separate from design teams, like when they don’t talk, and sometimes people have different biases, like your designer just wants to make something pretty for her portfolio but your salesperson is working on commission and so he’s trying to sell as much as he can, not really worrying about the quality. So, there are all these factors that weigh into that and that play into that.

- But I think I was always interested in the business side because if I could be involved in what we sold and what we pitched, then I could be confident that we sold the right thing, and if we win it, I can be confident that we can do the right thing for the client. I didn’t feel confident that—”Alright, if I feel bad about this… Well, I have the capacity to change it.” So, I would always ask to be part of sales meetings, I would always ask to be part of, “Can I see the contract? Can I help write the contract?” because, to me, that helped me make better design work later on. I wasn’t being handed things, I was being involved in that process. It’s the same reason that developers want to be involved in brainstorms. They don’t want to be handed a design and told, “Build this,” because what if you could do something better, but you’re already constrained by something artificially? So, I think that’s the reason.

- To me, it’s always been kind of a pragmatic approach to sales and the business side. I want to set the table as well as I can to do the best design that I can possibly do, and if a contract stops me from doing that, well, I have a control to write that contract, or I have the control to be involved in writing that contract. And if a brief artificially constrains me, well, maybe next time I could write the brief so that it doesn’t artificially constrain me. So, I feel like it’s a part of the design process to set the table for you to be able to do good design.